ETHNOCULTURE (Vol.2, 2010 pp. 45-53)

INTER-ETHNIC MARRIAGES IN KOREA

Hyup Choi

Chonnam National University

Introduction

Historically, Korea has been one of the world's few ethnically homogeneous nations. However, globalization and stark demographic trends have led to a dramatic change in terms of ethnic diversity in Korea. All the statistics indicate that more and more foreigners are coming to Korea in search of the "Korean Dream" and more and more foreign woman are marrying Korean men. A steep increase of international marriages between immigrant women and Korean men draws our particular attention as such phenomenon involves many anthropological questions. The purpose of this paper is to shed some light on this recent phenomenon of Korean men marrying immigrant women.

International marriages in Korea

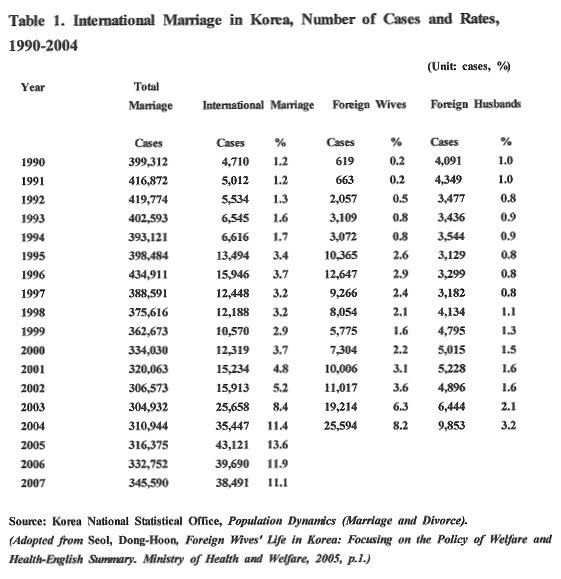

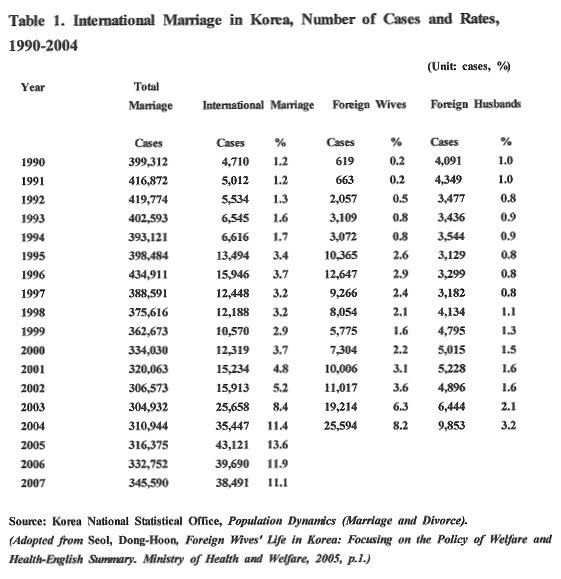

In 2005, international marriages accounted for 13.6 percent of all marriages in Korea, a dramatic increase from 1.2 percent in 1990. In 1990, there were 4,710 marriages between Koreans and non-Koreans, and most of them were marriages between Korean women and foreign husbands. In 2005, there were 43,121 international marriages, and this time the majority was Korean men marring foreign brides as 88 percent of the marriage immigrants were women. Table 1 reveals some interesting facts. First, the Korean men's rate of international marriage started to increase in 1992, when Korea re-established official diplomatic relations with China. Second, starting from 1995, the number of men participating in international marriages surpassed that of women.

Up until the 1980s, international marriages were largely confined to Korean women marrying foreign husbands, out-migrating after their marriage, and many of these marriages took place in the context of American military presence in South Korea (Yuh 2002). However, since the early 1990s, immigrant foreign spouses became a visible population in Korea. At first, most of the international marriage involved immigrants from China, but then the countries of origin of the marriage immigrants gradually diversified through time. In recent years, Vietnam is emerging as the most popular country for finding marriage partners.

It is also noted that the percentage of international marriage in recent years has been particularly high in rural communities, where demographic factors are forcing rural men to "import" brides from abroad. One rural county, Boeun-gun in Chungcheongbuk-do, became the first in the country to record an international marriage rate of 40 percent in 2005; out of 205 marriages registered there, 82 were international unions. Nationwide, 35.7 percent of all marriages that were recorded in rural communities in 2008 were international marriages, over half of which were between Korean men and Vietnamese women. Why is it, then, that the number of international marriages is growing especially rapidly in the countryside since the 1990s? To answer this question, we must examine several factors, international as well as domestic.

Factors affecting international marriages

a) Global structure and women's marriage migration

International migration is primarily driven by the migrants' motivation for

better economic opportunities, and globally an increasing number of women are

joining the stream of international migration. Thus, a woman's marriage can

be seen in the context of the structure of the global economy and of the social

realities of the countries involved. Therefore, factors to be considered involve:

(1) the uneven development among countries in the global economy and the consequent

encouragement of commercialization of women, (2) the migrants' country of origin,

particularly in reference to its government policies, that seem indifferent

to or even covertly encourage female migration so as to soften their country's

poverty and unemployment, (3) the destination country's eagerness to use international

marriage to solve the problem of limited availability of marriageable female

population in certain areas or class of people (Seol 2005:3).

Another factor is the influence of the so-called cultural globalization. Many scholars have pointed out that the influences of the mass media, commercial trade, and other material and cultural exchanges reduce the psychological distance among countries and stimulate interest in possible countries of destination (Piper and Roces 2003; Teo 2003).

b) Rapid industrialization and changes in rural communities

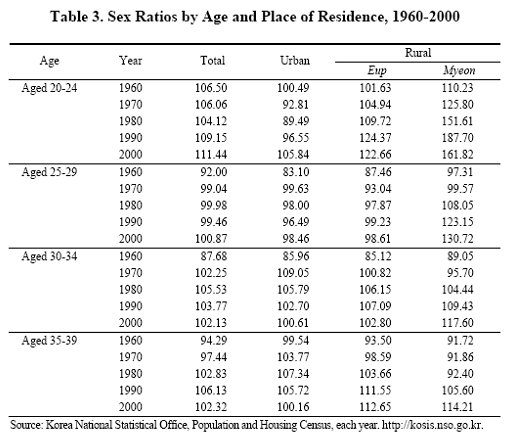

After three decades of rapid industralization and phenomenal economic growth,

many Korean rural communities are, instead of enjoying the fruits of economic

growth, facing hard realities. Demographic imbalance, social disintegration,

and value conflicts are some of the serious problems rural communities face

today. The most noticeable change in rural Korea since 1960 has been that of

population change. On the whole, population movement since the 1960s was characterized

by rural desertion and urban concentration. According to census data, the rural

population of Korea in 1960 was 72%, whereas it was reduced to 26% in 1990.

Rural-to-urban migration was relatively heavy among young, working-age population

as evidenced by the increase in the dependency ratio of the rural population.

The census data show that the rural areas reached a dependence ratio of 107.3

in 1970 from a previous ratio of 98.0 in 1960, an increase of 9.4 points. Interestingly,

according to demographer Taewhan Kwon, in the 1980s, it is estimated that about

40% of females in the 18-24 age group left their original rural communities

for urban areas (see Table 3).

This, of course, has affected the age-specific sex ratio of rural communities. At any rate, this population change has brought about a series of related consequences: chronic labor shortage, increased labor participation by women and the aged, increased mechanization in farming, etc. But more importantly, it has caused a disruption of traditional social organization and structure. Finally, it should be pointed out that rural desertion has something to do with changes in values and expectations. Traditionally, farmers enjoyed relatively high social standing, occupying the highest rank level among commoners, just below the ruling "yangban" class. Occupations related to manufacturing and commerce were given a lower social standing. Therefore, even poverty-stricken farmers had the view that "farmers are the mainstay of the country." The situation, however, has changed tremendously. During the years of rapid economic growth, the highest development priorities have always been given to industrial growth and urbanization. As a result, the social standing of agriculture as an occupation has been much degraded in contemporary Korean society. With industrialization and urbanization, the higher income and better educational/cultural opportunities available in the cities have increasingly given more prestige to urban life. Consequently, farmers and rural youth have lost the psychological satisfaction derived from involvement in agriculture. In fact, many farmers today concede that their living conditions have improved in the recent decades. But they do not want their sons to enter farming. According to recent surveys, only a small percentage of farmers express a willingness to recommend farming to their children.

c) Demographic factors

The traditional Korean value system leads to a preference for male children

over female children. This preference of boys over girls has been a significant

factor in the sex-ratio imbalance of the Korean population, as Koreans have

been conducting illegal sex tests on fetuses that often lead to feticide. As

a result, and as also illustrated in Table 3 above, there is a serious imbalance

between males and females of marriageable age.

d) Social environment

A more direct factor explaining the rapid expansion of international marriages

in Korea is the institutionalization of marriage brokers (Han and Seol 2006).

As international marriage brokerage is a lucrative business that requires little

initial investment, many brokerage firms have sprouted rapidly in recent years,

and government regulations overseeing the sector have fallen behind the pace

of its growth, consequently leaving the activities of the firms virtually uncontrolled.

This kind of activity caught the attention of an American reporter in Hanoi,

and his story was published in the February 22, 2007, issue of the New York

Times under the title of "Korean Men Use Brokers to Find Brides in

Vietnam." The piece argues that the marriage-broker industry is seizing

on an increasingly globalized marriage market and sending comparatively affluent

Korean bachelors searching for brides in the poorer corners of China and Southeast

and Central Asia.

As a consequence of these "marriage tours" marriage to foreigners

in South Korea has experienced an explosive growth.1

e) Government policy

Another factor supporting international marriage involves the explicit and implicit

policies of the central and local governments of Korea. Demographic conditions

(i.e., shrinking birth-rate and unbalanced sex-ratio) are an underlying force

influencing these policies. Some local governments in rural areas sponsor international

marriages through sister-town relationships or through the help of brokerage

firms. Many local government offices, mostly in rural areas, are now running

Korean-language or cooking classes designed to socialize foreign wives into

the local community. The central government revised the Nationality Act, the

Departures and Arrivals Control Act, and related laws on social welfare, so

as to provide a systemic footing for a married immigrant to legally stay and

live in Korea. The central government has also developed some immigrant-friendly

policies, such as supporting organizations which advocate for the human rights

of immigrants (Lee et al. 2006:171).

Marriage immigrants: Some characteristics and problems

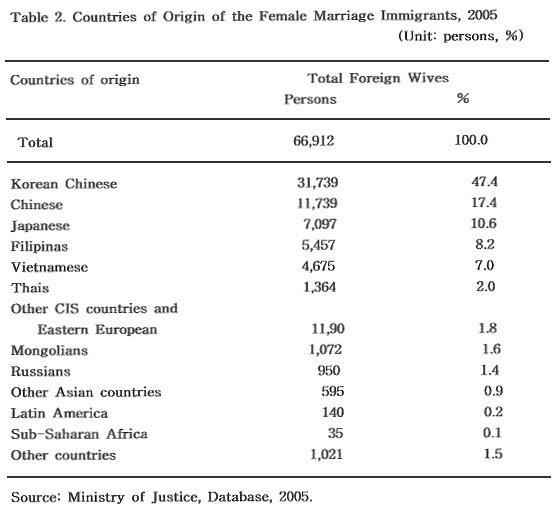

About 60 percent of the foreign wives in Korea are from China, and many of them are ethnic Koreans, as China has a large ethnic Korean population in its northeastern region. Another 20 percent of foreign wives are from other Asian countries, especially Vietnam, the Philippines and Thailand, and their number is on the rise in contrast to the decline of the number of foreign wives from China. According to some marriage agency, provincial bachelors prefer Southeast Asian women despite their racial differences because ethnic Korean women from China have acquired the reputation of "melting away" into the cities to work on their own after using their new husband to obtain a visa. Unlike the Southeastern Asians, the ethnic Koreans can speak Korean rather fluently, and have no problems in adapting to Korean culture. Therefore, they can be quite independent from their Korean husbands, and easily integrate into the fabric of Korean society in a short period of time.

According to a survey conducted in 2005, a majority of foreign wives reported that one of their primary motives for marrying abroad was an economic one (Seol 2005). However, for ethnic Koreans living in the regions of northern China and the former Soviet Union, an additional migration incentive might be their ethnic ties to Korea. Yean-Ju Lee and others examined the divorce rates among married immigrants. The divorce-separation rate is the highest at 13 percent among Korean Chinese wives, and the percentage of differences is statistically significant only with Southeast Asians, among whom only two percent were divorced or separated (Lee et al. 2006:177). This finding raises questions on whether marital breakup may reflect either family values or the foreign wives' control over their own lives. Korean Chinese and Chinese wives tended to have high employment rates, near 40 percent, whereas that of Southeast Asians was 26 percent. This difference may be due to Southeast Asians' poorer command of the Korean language, heavily rural residence, lower divorce rate, and younger ages (ibid. 178). However, the authors of the study concluded that "if Korean Chinese are the most autonomous, Southeast Asians are the most adaptive to the host society. Their observed rates of Korean citizenship and employment are lower than those of Korean Chinese, but once length of residence in Korea and Korean proficiency are taken into account, the rates are no longer significantly different" (ibid. 179).

The problems of immigrant wives are wide-ranging and complicated. Some of the mostly cited problems foreign wives face are economic hardship, the language barrier, and domestic violence. To deal with such problems, institutional and legal changes in central as well as local government guidelines are needed. An indication of the government's willingness to bring about changes vis-à-vis international marriages can be sensed in many areas. For example, the government recently changed the official classification of marriage between Korean men and foreign women on all government documents and manuals from "a family of female married immigrants" to "a multicultural family." Through this change, it is hoped to shift the focus from the migrant's adaptation to Korea to a mutual international understanding. In the past, programs offered at migrant support centers were heavily focused on educating foreign wives about Korean customs. But new policies stress that the husbands, their families and society must also understand and embrace ethnic differences.

Consequences of international marriages

For years, Koreans have clung to the myth of racial homogeneity. The idea was evident in common Korean expressions applied by Koreans to themselves, such as: "danil minjok," or "unitary race" sharing the blood of one ancestor, Dangun, who founded Gojoseon, now Korea, in 2333 B.C. In a country with such a strong sense of ethnic homogeneity, the sudden surge of international marriages brings about a new reality with which Koreans must cope.

a) Rise of mixed-ethnicity Koreans

A report commissioned by JoongAng Ilbo on the long-term impact of international

marriage indicated that the Korea of the future may be very different from the

one we know now.2 According to the report, Korea's multicultural population,

which currently stands at roughly 35,000, will climb to 1.67 million by 2020.

By 2020, one in five Koreans under the age of 20 will be of mixed ethnic heritage,

as will be one in three newborn.3 Thus, it is evident that the greatest

impact of the increased number of international marriages will be the drastic

increase in the number of Koreans of mixed ethnicity.

There are growing signs that Korean society is making some progress in accommodating such changing trends. For instance, one recent survey revealed that over half of Koreans, both male and female, would be open to the idea of marrying a foreigner. Perhaps even more surprising, another survey indicated that over 60 percent of parents would be willing to accept their son or daughter marrying a foreigner. It might not sound like much, but in a nation that has long valued its "pure bloodlines," the survey results, if anywhere indicative of social attitudes as a whole, would suggest that major changes in social views are underway. Naturally enough, one casualty of these demographic changes is the ideology of "one homogenous race." For decades, Korean elementary and middle school history and ethics textbooks stressed that Koreans were for 5,000 years "one pure race." Not only was this, at best, of questionable historical validity, but it served to alienate Korea's mixed-race population, which felt the concept marked them as "impure" and "foreign." The current administration, however, has decided to do away with the concept of ethnic homogeneity in future textbooks in a bid to better embrace Korea's multiethnic community. What's more, some sociologists predict that you may soon see the idea of the "hyphenated Korean" become universal. As one sees in the United States, where people often identify themselves as "Irish-Americans," "Italian-Americans," and so forth, Koreans may soon use hyphenated terms like "Vietnamese-Korean" and "Filipino-Korean" to refer to individuals of mixed extraction. Recently authorities decided to abandon the Korean term honhyeol (literally, "mixed blood") to refer to multiracial people in favor of the term "multicultural individuals." Not that everyone has such a rosy outlook on things. Some question Korea's ability to embrace increasing numbers of immigrants and their children, and express concern about possible ethnic clashes similar to those witnessed in various Western nations.

Another factor which facilitates Korea's internationalization in terms of its demography is foreign labor migrants. As Korea's birth rate is the lowest among the OECD nations (1.08 in 2005), Korea's population is expected to shrink from its 48 million to 40 million by 2050. The resulting aging of the society and reduced size of the nation's economically active population requires the acceptance of a foreign work force. A 2000 UN report on replacement migration warned that Korea would need 6.4 million foreign workers between 2020 and 2050 to keep its economically active population at 36.6 million. The growing number of international marriages and the continuous influx of foreign workers, combined together, would act as a powerful social force that must be considered in the future. The potential social and political implication of this cannot be ignored. Some sociologists predict that should mixed-race and/or foreign-born Koreans congregate as a single social and political block, their rising numbers could allow them to wield increasing social and political influence, much akin to that of the Hispanic community in the United States.

b) Ethnic communities

Multiculturalism in Korea is a rather new phenomenon. Therefore, Korea has not

yet seen the development of large-scale foreign ghettos like the immigrant ghettos

of some Western nations. Despite this, ethnic neighborhoods are starting to

take shape throughout Korea. You can see this in Seoul’s changing urban

geography. A "French village" of sorts has developed near the French

School in Seorae Village, Banpo 4-dong, Seocho-gu. A "Little Tokyo"

has popped up in Ichon-dong, Yongsan-gu, and Yeonnam-dong, Seodaemun-gu, has

turned into a Chinatown, while Central Asians, Mongolians and Russians have

carved out their own community in Gwanghui-dong, Dongdaemun-gu. In Itaewon-dong,

Asian and African Muslims have settled in the vicinity of the neighborhood's

majestic hilltop mosque, and Chinese Koreans have gravitated toward Garibong-dong

in Guro-gu, Daerim-dong in Yeongdeungpo-gu, and Gasan-dong in Geumcheon-gu,

where they've established whole neighborhoods full of Korean-Chinese shops and

businesses.

Concluding remarks

International marriage in Korea has increased drastically since the 1990s. Although international marriages have grown in numbers for Koreans of both sexes, men are two or three times more likely to marry a foreign woman than are women to marry a foreign man. The demand for foreign spouses seems to be greater in certain segments of the population, especially among young rural men. The main characteristics of international marriages in Korea can be summarized as follows: it is mostly Korean men who seek wives from less developed countries; significant number of the couples are arranged by commercialized marriage brokers (or agencies); the majority of the men are rural and economically not affluent.

As the international marriages have challenged the "homogeneous" and "patriarchal" Korean society, the central government had to take action. In 1997, the government revised the Korean Nationality Law, abolishing patrilineal and gender discriminating rules. In April of 2006, the government announced the "Grand Plan." The "Grand Plan" has two very important policy implications marking a shift from the old orientation: 1) from the policy focusing on "them" to one that focuses on "us"; 2) from a policy for "women" to a "family" policy. The first shift is especially important, since it comprehensively covers the whole processes of adaptation of internationally married families and their children, including pre-immigration policies as well as guidelines applying to later stages of their residence in Korea (Lee n.d.).

Korean society is now facing the challenge of becoming a multicultural society. As economic and cultural globalization processes continue, catalyzing social and political adjustment through trial and error, the myth of the "unitary race" and of "homogeneous Korea" will soon become things of the past.

NOTES

1. In 2006, for example, 40 Vietnamese women became residents of the Haenam County of South Jeolla Province after the county offered 5 million won (about US $5,380) in wedding subsidy per single man as part of its "Program for Marriage of Rural Single Males." However, although Haenam County budgeted 150 million won for the wedding subsidy, it planned to spend only 21 million won total, as some of the subsidies were just transferred directly to international marriage brokers. A Haenam County council member complained that the county program for the marriage of rural bachelors is turning into a cash-maker for marriage brokers (http://english.hani.co.kr/popus/print.hani?ksn=214674).

2. We are already getting a taste of things to come. In Jeollabuk-do, 755 multiracial students are enrolled in area schools. At one school, Mupung Elementary School in Muju-gun, four of the incoming eight first graders are multiracial.

3. Rural communities have already entered the stage of "super-aged societies"; in 2004, some 29 percent of the population of Korea's rural communities was over the age of 65. The relative lack of social infrastructure in the countryside has led the few young women who still live there to avoid marrying rural men. With these trends working against rural communities, the mass immigration of foreign women as brides is not only necessary to maintain the local tax base and labor pool, but also essential in ensuring the survival of the communities themselves.

REFERENCES

Han, G.S. and D.H. Seol. 2006. Matchmaking Agencies in Korea and Their Regulation Policies (in Korean). Gwachon: Ministry of Health and Welfare.

Lee, Hye-Kyung. n.d. "International marriage and the state in South Korea." mimeograph (files of the author).

Lee, Yean-Ju, Dong-Hoon Seol, and Sung-Nam Cho. 2006. "International marriages in South Korea: The significance of nationality and ethnicity." Journal of Population Research 23:2: 165-182.

Piper, N. and M. Roces. 2003. Introduction: Marriage migration in an age of globalization. in N. Piper and M. Roces (eds), Wife or Worker?: Asian Women and Migration. London: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Inc. pp. 1-22.

Seol, Dong-Hoon. 2005. Foreign Wives' Life in Korea: Focusing on the Policy of Welfare and Health - English Summary. Gwachon: Ministry of Health and Welfare.

Teo, S.Y. 2003. "Dreaming inside a walled city: Imagination, gender and the roots of immigration." Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 12(4):411-438.

Yuh, J.Y. 2002. Beyond the Shadow of Camptown: Korean Military Brides in America. New York: New York University Press.