This lesson explores the characteristics of scholarly articles that you’ll be asked to use in your academic research. By the end of this lesson, you’ll be able to:

Scroll down to continue

Take a moment to think about the articles that you know. What sort of articles are they? News articles? Special interest stories? Blogs? How do you access these articles? Do they appear in print magazines? On the internet? What characteristics do they exhibit?

Now try to think about the vast number of articles that exist. Think not just in the present, but also historically. For our purposes, this collection can be divided into three categories: scholarly journal articles, trade publication articles, and popular articles. These divisions are defined by the audience for whom they are written:

Each of these categories exhibit additional characteristics that are determined by/tailored to their specific audience. Take a moment to review how their authors, purpose, and other key features differ. Then, return to this lesson and we’ll focus on specifics of the scholarly articles category.

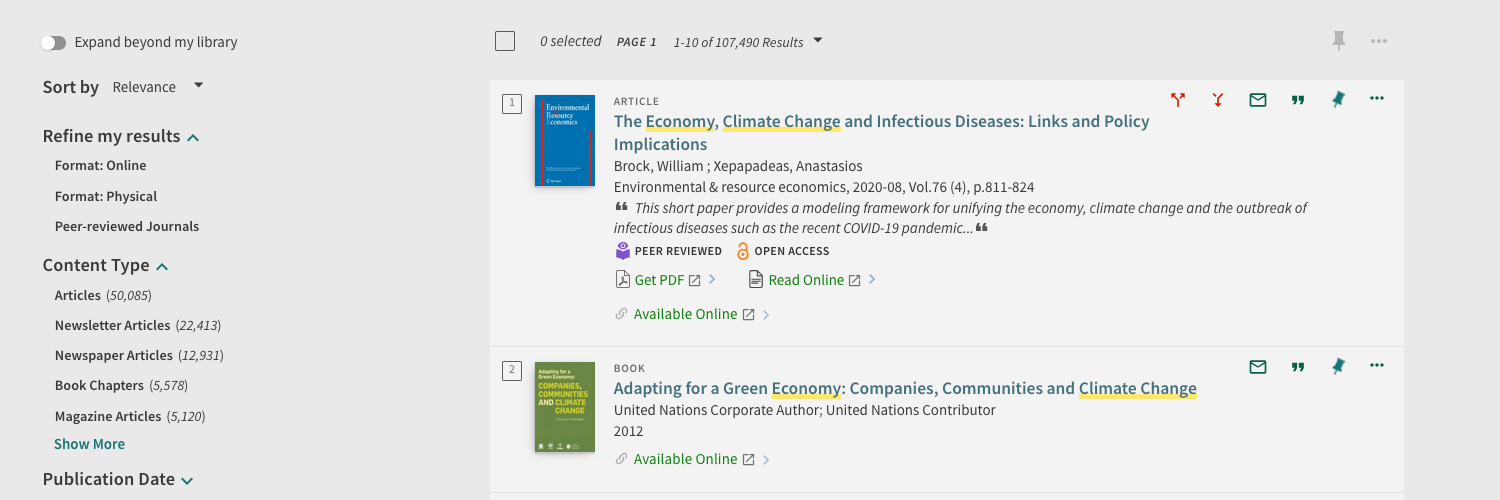

A common question from students is how to tell if an article is scholarly. Seasoned researchers will recognize articles from certain scholarly titles that are popular in the field, but students don’t typically have the amount of experience to do so. You could use the filters that are available in many library databases to narrow your search results to scholarly articles. However, most scholarly articles also have the following defining features.

Scholarly articles are generally written by those who have performed the research written about in the article. You’ll almost always find an institutional affiliation—this can be a university or other research facility—listed along with the author.

Scholarly articles are written for a limited audience—usually others engaged in similar research in the discipline—as a means by which researchers inform their peers of recent discoveries or comment on previous research. Since they are written for peers, scholarly articles contain specialized language or jargon unique to the discipline.

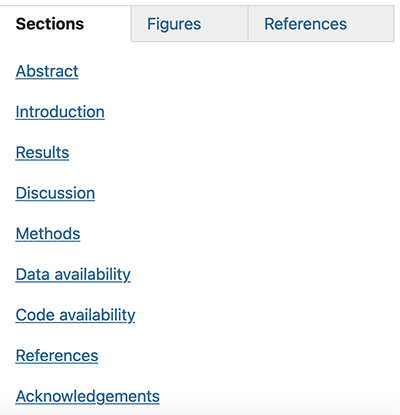

Many scholarly articles (particularly those in the sciences), are split into sections that define different important components (e.g., methods, results).

Even if an article is not broken into sections, there are still markers that can be used to determine if it’s scholarly in nature. The following characteristics are common in art and humanities research:

Scholarly articles contain a formal means of citing other works that have informed the published study. While citation formats differ, all contain a means of citing both within the text and via a dedicated section at the end of the article.

There is a lot of specialized vocabulary associated with scholarly articles that, depending on the discipline you’re studying, you may be required to understand. In this section, we’ll briefly present the most common terms (mainly from the sciences and social sciences). Explore each below.

Empirical articles report on original research (as opposed to a review of existing studies). In the sciences, they are synonymous with primary source literature. See the following slideshow for more information on recognizing empirical articles.

Review articles explore, summarize, and analyze the existing literature on a topic. They do not report on any original research and are considered secondary source literature. In fields like health, there are different examples of review articles (e.g., systematic reviews).

Primary source literature contains first hand accounts. Examples differ based on the discipline being studied. In the arts, primary sources consist of the original work (not a reproduction). In literature, a novel as written by the author (without commentary) is a primary source. In history, examples of primary sources are diaries, speeches, and other documents created at the time of a specific event. In the sciences, primary sources report original findings of a new study (empirical articles).

Secondary sources reflect on, summarize, provide commentary, or analyze primary sources. Examples of secondary source literature includes a commentary on a novel or work of art, an historical work that attempts to comprehensively recreate an event (drawing on many primary sources), or a review of existing literature on a topic.

Quantitative methods “quantify” relationships between variables that are present in a given population using statistics. Think numbers, although not all quantitative studies use numerical data. Examples of common quantitative methods include experiments containing experimental and control groups, sample surveys, questionnaires, etc.

Qualitative methods “qualify” or describe experiences and perspectives to develop meaning. Examples of common qualitative methods include open-ended questions, interviews, field observations, and case studies.

Mixed method approaches utilize multiple sources of data or multiple research methods (often a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods) to investigate a research question. It is said to enhance confidence in findings because there is not an overreliance on one particular research method that could affect interpretation.

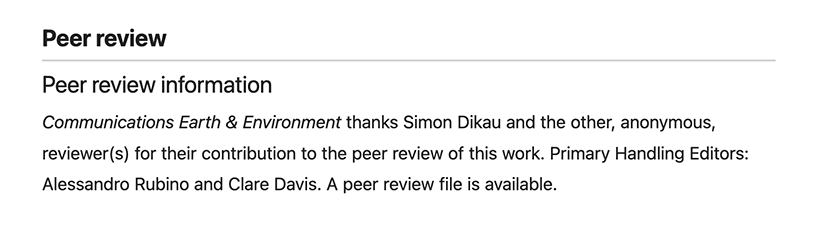

Peer-reviewed articles have undergone a process by which subject experts (other researchers in the field) have evaluated the work for originality, soundness of methods, and contributions to the overall literature on a particular subject prior to publication. Peer review is often used by student researchers as a filter, a marker of quality. Peer-reviewed literature is seen as more credible than literature that has not undergone peer review. Peer-reviewed articles are often called refereed articles. It’s important to note that not all scholarly articles are peer reviewed.

An abstract is a short summary of the paper that includes information on why it was written, a brief overview of what was done, and key findings. An abstract allows the researcher to identify key points of the study and determine if it is relevant to their topic. Many library databases make article abstracts available in their results pages.

The literature review section provides an overview of the research that has already been performed on a subject, situating the study within the existing literature. It may be combined with the introduction section.

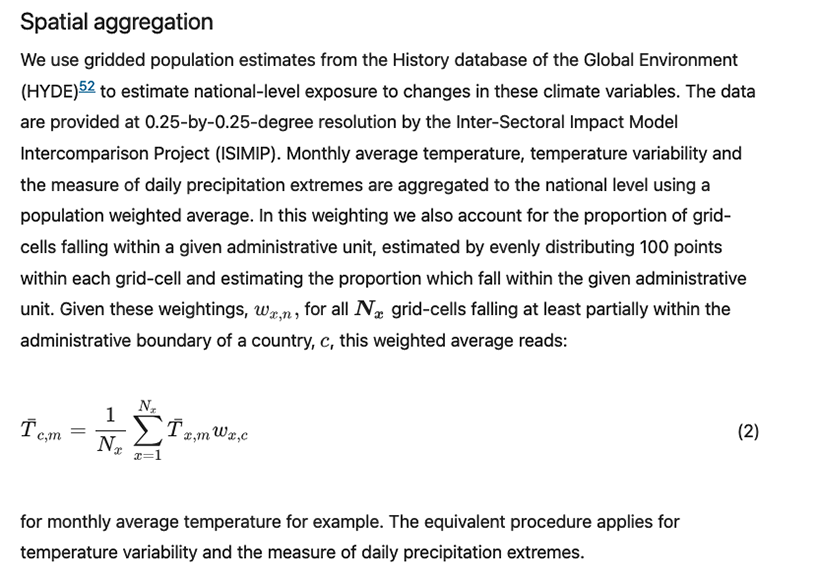

The methods section details how the actual study was designed and conducted. Sample demographics, specific methodologies used, data collection, interpretations, etc. are addressed in this section.

The results section details what the study found.

What are the implications of the results? Are there any areas where the current work is lacking or further studies are needed? The discussion section considers the results in the context of the scholarly conversation and sometimes identifies next steps.

The works that influenced the current study are listed and given the proper credit in the reference section. The formatting of this section will differ depending on the field of study and its accepted citation format. From a researcher’s perspective, reference pages can be a useful tool for identifying additional, related articles.

Scholarly articles are best found through the library’s subscription databases. While it has become more common to find scholarly articles through search engines, beware of paywalls that ask you to pay for content. If you are an EMU student, you should never pay for an article or book—chances are that you have access (either directly through the library’s subscriptions or through services such as interlibrary loan).

Be wary of using generative AI tools to find scholarly articles. These models are trained on a very limited portion of the scholarly literature, typically open source material that is freely available on the web and not subscription content. They are also prone to what is called hallucination, where they create resources that don't actually exist.

Finally, it is important to note that not all resources in library databases are scholarly in nature. Many library databases will provide access to news and popular content, as well as other resources such as books, videos, etc. When possible, learn how to use a database’s filters to limit to scholarly or peer reviewed articles.

You don’t always read academic articles as you would a popular article—linearly from front to back (or top to bottom). One popular method of reading scholarly articles uses the sections mentioned earlier. Knowing what to find in each section allows researchers to skim quickly, helping in their determination as to whether a source is relevant.

Now let's apply what you've learned. Answer the following questions.

1. Select all that are true. Peer review:

2. Select all that apply. Empirical articles:

3. Select all that are true. An abstract:

4. True/false. You should always read a scholarly article as you would a good book–completely from front to back.

5. The peer review process:

6. Qualitative research methods rely on:

7. If a study uses both qualitative and quantitative methods, it is called:

8. Which of the following is considered a secondary source?

9. Select all that apply. Which of the following can be used as an indicator that an article is scholarly in nature?

10. True/false. Library databases only contain scholarly articles.

Bill Marino

Professor, Online Learning Librarian

Eastern Michigan University

[email protected]

(734) 487-2514

Last updated: April 2025