Faculty Development Center Teaching Blog

Please email us at [email protected] if you would like to propose a topic, or if you would like to submit something to the FDC Teaching Blog.

April 11, 2022

Teaching Study Abroad by Ron Delph, Professor and Graduate Coordinator of History and Philosophy

One of the absolute highlights of my career at Eastern has been teaching students in study abroad programs run by the university. A few years back, in 2004, I launched my own study abroad program, “Power, Place and Image in Florence and Rome.” In this program, students travel with me to Italy, where for eight days over our winter break we study the history and culture of Florence and Rome in the later Middle Ages and Renaissance eras. I’ve been fortunate enough to take students to Italy with me on this program seventeen different times over the years. Hands down it’s the best thing I do as a teacher at Eastern.

I enjoy teaching in Florence and Rome because of the shift that takes place in my pedagogy. Teaching in a brick and mortar setting on campus, I find myself struggling to get my students to appreciate that the people who lived in the past, whether in ancient Rome or in the fourteenth, fifteenth, and sixteenth centuries, perceived the world differently than they do. Their values were different, their perception of their place in the world, and their relationship to the world were all different from how students in the twenty-first century understand and perceive these things. My ability to draw upon a wealth of historical artifacts, ruins, paintings, monumental buildings, statues, and the urban landscape to illustrate these differences enables students to quickly grasp just how foreign to them were the ways in which the people of the past perceived their world and carried out their lives.

From a pedagogical standpoint, there are several other advantages that I’ve come to appreciate while teaching in Florence and Rome. First off, surrounded by students in the Roman Forum while I’m talking about the Roman Empire, I don’t have to struggle to convince students of the importance of what I’m lecturing on. Similarly, as students gather around Michelangelo’s magnificent statue of David and I begin to lecture on why this statue came to represent the fierce republican sentiment of the Florentine people in the early sixteenth century, I don’t have to work to capture their interest or hope they are paying attention to what I am saying. Students just devour the material. Best of all, I don’t have to use PowerPoints!

One of the toughest parts about teaching my course in this study abroad program is actually the abundance of material that I have at my fingertips. Rome and Florence both have such rich histories, not just during the later Middle Ages and Renaissance eras, but from antiquity all the way through up to the modern era. I learned early on that for my course to succeed, I was going to have to make some very brutal, heartbreaking choices about what I just couldn’t talk about.

As a teacher, it’s my job to help students make sense out of the history that unfolded in these two cities in the later Middle Ages and Renaissance eras. In order to do that, I have developed several themes that give me the flexibility I need to lay out developments in the political, social, religious, and cultural realms in both cities in these eras. Once I had identified the themes to use to explore these areas, then I began to look for the monuments, ruins, works of art, statues, palaces, bridges, and streets that would allow me to illustrate my ideas. I built each day’s set of lectures and tours around these themes and accompanying artifacts and pieces of the historical record. But it’s hard to just walk by some jaw dropping work of art or ignore some of my favorite sites and streets in these cities because they don’t fit into the themes I’m developing.

The learning that takes place on this trip goes far beyond the material that is covered in the lectures however. Both Florence and Rome are vibrant, thriving European cities, pulsating with life and culture. Students are not only exposed to the past in these towns, they are immersed within the present, and this present is a southern Mediterranean, European culture which is quite different from their own in many ways.

Every street, every restaurant, every market, every shop, holds a new experience for them. They see people dressed differently from them, talking differently from them, eating food that is different from what they are accustomed to. They see public transportation that works spectacularly well, they learn what a walkable urban landscape looks like, and they begin to appreciate the value in restoring old buildings instead of tearing them down. And along the way, it slowly begins to dawn on them that there are other, viable ways of doing things than what they have been exposed to back home.

For most of the students who participate in my study abroad trip to Florence and Rome, there is a tremendous amount of personal growth that takes place as well. Many of them have never been out of the country before and many of them have never flown on a plane before. This trip not only offers these students the opportunity to experience any number of such things for the first time, it does so in a safe, friendly environment. And it doesn’t take long for the students to screw up their courage and begin going out on their own in the late afternoons and evenings when the program is over, exploring and shopping and meeting Italians. By the end of our stay in each city, they have become very comfortable with getting around and foraging on their own. Their confidence soars as their ability to navigate the streets, markets and shops grows.

Another area of personal growth for the students on this program is the numerous, sometimes life-long friendships that they develop with other members of their group. These friendships last because they are built upon some pretty stupendous shared experiences. What really warms my heart, however, is when I think of the two sets of couples who met while on one of my programs, and are now married. Talk about a life-changing experience!

I can’t guarantee you will help your students find love, but perhaps, in a far-off place, you can help them find powerful moments of learning.

April 4, 2022

I Taught Good, But Boy Did They Learn Bad! by Jeffrey L. Bernstein, Professor of Political Science and Director of the Bruce K. Nelson Faculty Development Center at EMU

Opening Day of baseball season is this Thursday. Those of you who know me will realize is one of the most festive and holy days on my calendar.

As a political scientist and lifelong baseball fan, I appreciate Dwight Eisenhower’s remark that being President of the United States and managing the hometown baseball team are the two jobs that everybody thinks they can do better than the person currently doing it. I resemble this remark, particularly concerning the New York Mets, with whom I have a lifelong love affair. I long ago gave up the vision that I could someday play for the Mets, but still spend a lot of time imagining what it would be like to manage them. Suffice it to say, I have strong opinions.

In his book I Managed Good But Boy, Did They Play Bad, the late Jim Bouton, noted pitcher and counter-cultural baseball iconoclast, celebrated some well-known (and lesser-known) managers throughout history. The lament contained in the title – that they managed well, but the team did not respond – is a common one, which has always made me think about teaching. How often have we lamented the fact that we taught the material effectively and yet our students seemed not to have learned what we wanted them to learn? How often have we looked through exams and papers and complained about students who simply were not doing what they were supposed to do? What if we “taught good” but they actually “learned bad?” We’ve all been there.

To be fair, sometimes we do teach well, our students don't learn the way we would like them to, and the fault is not with us. Just as the best manager in the world cannot bend down to stop a little roller up the first base line from going between his fielder’s legs, it is hard to blame the instructor if a student skips class, or does not do the reading, or blows off studying for the exam. As I frequently tell my students, I can only meet you halfway: I can't offer wake up calls in the morning, nor can I sit there as you study and force you to focus on course material rather than on the social media apps on your phones.

Often however, there is a disconnect. We do what we believe to be effective, our students do what they should do, and yet, our students do not learn as well as we would like them to. While we could sit in the comfort of the dugout (our offices) and blame the players on the field (the students), a more productive approach might be to ask ourselves if we could approach things differently to enable our students to succeed. That is where the job of the baseball manager and the teacher coalesce – our job is to position the players in the field, or the students in the classroom, to do their job well, and maximize their chances of success. We cannot learn for our students, just as baseball managers cannot throw the nasty curveball for strike three, but we can create conditions to maximize the likelihood that learning will occur.

As our colleague John Koolage noted in this space last week, effective teachers spend a lot of time in the act of assessment, specifically using student work to determine if they are achieving the learning goals they have for their students. Sometimes, we succeed. If we do not, our next step should be to consider how to change our instructional practice in a way that will support the learning goals for our students.

Doing so makes us vulnerable. It is not easy to admit that, despite our best efforts, we have not succeeded. I’ve had to do this, and it is incredibly hard, especially when you pride yourself (as I do) on your teaching. But we are not infallible, and we must accept that sometimes our best efforts fall short. This is a struggle, but also an opportunity: interrogating our less successful moments enables us to improve upon our teaching in profound ways.

With this said, I would argue that there is a missing piece of this equation, the student voice. I have spent much of my career arguing that we ought to give more attention to student voices in striving to understand student learning. Inspired by the work of Carmen Werder, Peter Felten, and others, I have maintained that we have much to gain by bringing students into this conversation. This can take the form of having students assist us as quasi-teaching assistants, or formally soliciting midterm feedback from students, or even just stopping class one day to ask how things are going.

I’ve done all of these, and learned a great deal from listening to my students (and am happy to facilitate your doing the same!). While students likely have no basis to judge my expertise in my field, there is nobody better than my students at determining whether I stimulated their interest in the course material, or whether I created a welcoming classroom environment where students felt as if they belonged. In these matters, the student voice is of paramount importance.

As you wrap up this term and think about the next one, I urge you to consider how you will incorporate student perspectives into your teaching and learning. Involving students in these conversations will be a central goal of the Faculty Development Center next year; I invite you to join us as together we explore the positive outcomes that will arise from these important conversations. As we consider what we can do to improve our students’ learning, I hope we will consider how their voices can help us assess the effectiveness of our practice, and how we might find ways to do even better. Let us resolve to not only teach well, but also to have our students learn well.

Thanks for listening.

March 28, 2022

Let's Talk about Assessment (and Bruno) by Dr. John Koolage, Professor of Philosophy and Director of General Education

Wow! Still reading? Assessment is not a concept that really draws, nor holds, the attention. I have the, perhaps reasonable, fear of being the person who provided the dullest blog post ever, but there is a crisis in assessment. This crisis is a direct result of lack of clarity. While the side eye is certainly warranted by some uses of the term, it is not in others. Here, I hope to make some distinctions that will increase our understanding of assessment and its role in supporting student learning – something we all care about.

One of the greatest challenges in developing adequate assessment is that the term is ambiguous. While some conceptions of the term correctly draw our ire, others should not. A simplified model of teaching can help us zero in on a handful of fruitful concepts of assessment. This model proposes four constitutive elements to teaching: (1) how we would like students to be different when they are done their time with us; (2) what we will do together to help students be different in this way; (3) how we will know if they are different in the way we want when they are done with their time with us; and (4) the context in which (1), (2), and (3) occur and are understood.

For example: I would like my students to (1) remember a handful of philosophic concepts. So, I will (2) deliver a lecture on these concepts (exciting, right?). Then, I will (3) ask them a couple of questions that require them to recite a few details of these concepts, and I will also observe whether they are taking notes and paying attention throughout the lecture. This model can be extended to all learning activities (a common name for (2) that take place in a moment, as part of a class period, the whole class period, multiple weeks of a course, a whole course, linked courses, whole programs, all the way to completed degrees. My focus here is the part of the model identified by (3) – how will we know if learners are different in the way we intend by teaching them – namely, assessment.

Assessment can serve many purposes. These purposes can be institutional, such as grading, or folk psychology, such as predicting student engagement in upcoming classes, but my focus here is student learning. When assessment is leveraged for the purpose of student learning, our assessments are aimed at improving learning activities – this is sometimes called "closing the loop." When we close the loop, assessment is aimed at improving our learning activities (tests, journal assignments, papers, group activities, lectures, reading lists, etc.), thus improving students’ opportunities to engage in meaningful growth. When one has the feeling that a particular activity needs to be tweaked to better target the learning in question, one is engaged in assessment.

Changing a learning activity in order to better target a particular skill, content knowledge, disposition, or anything else, is closing the loop. Loop closing is iterative; this is known as "continuous improvement" in teaching and learning circles. Understanding the purpose of assessment is critical to the decisions we make about it – it is difficult to see what could be upsetting about taking stock of our own role, and refining and improving it, for the purpose of increased student learning.

Assessment of student learning comes in many flavors. Here, I want to draw two distinctions: Direct vs. Indirect Assessment and Formal vs. Informal Assessment.

The direct versus indirect distinction has to do with the “distance” one is from the demonstration of learning (sometimes called the artifact). Consider a journal assignment wherein students reflect on their use of course content in their own lives. The journal they produce is the artifact. If we use this artifact to determine whether the student learned some skill (say, journal writing), we would be doing direct assessment – learning is assessed, directly, by way of the journal.

Now, if we were to ask the student whether they believed they learned the skill demonstrated in the journal assignment, we would be doing indirect assessment. Here, the "measured" learning is one step removed from the artifact (the demonstration of learning). While the philosopher in me worries about this distinction, it draws a helpful difference between, say, a survey of students’ perceptions of learning (indirect) and (direct) assessments of performance (artifacts). Current best practices in the assessment favor direct assessment.

The second distinction is formal versus informal assessment. Informal assessments involve “eye balling” student learning. If you have ever looked to see if your students are taking notes in class, you have done an informal assessment of student learning. In formal assessments, you develop the measurement of learning (usually a rubric) in advance of collecting the artifact. Unsurprisingly, it is formal assessment that finds its way into the scholarship. That said, both formal and informal assessments can be extremely helpful in the pursuit of continuous improvement.

Alright, kudos to you for reading this far! Edge of your seat, I bet. Permit me a few more observations. First, the artifacts that we develop for assessing student learning can also meet other goals: grading, for example. Two for the price of one! We can collect data that enables us to continuously improve learning activities while we accomplish other important teaching tasks.

Second, there are a number of psychological biases, including but not limited to confirmation bias, the self-serving attributional bias, and naïve realism, which can make assessment a real challenge. While bias is (probably) inevitable, it can be reduced, in the service of continuous improvement, by iterating assessment and working as a team (hopefully one designed to ensure diversity and inclusion). Additionally, methodological and theoretical pluralism– measuring in different ways, or with different assumptions, or different theoretical frameworks, can help too. That said, “eye-balling” student learning can still lead to great gains in terms of the continuous improvement of learning activities.

Assessment is a vital component of all good teaching. While I strongly believe that formal assessment, conducted by groups, using a variety of artifacts, is the key to programmatic assessment, I didn’t make that case here. Here, I only sought to suggest that you are probably in favor of assessment, under at least some descriptions. Cheers!

March 21, 2022

In the Middle by Genera Fields

Genera (they/she) is the current Graduate Assistant for EMU's Women's Resource Center. They are completing their first year in the Master of Social Work Program and hope to open a community center that provides holistic support in the future.

Binaries suck. There’s no way of getting around it. Either we are right or we are wrong, we pass or we do not. We must choose to identify with something or not identify with it, whether we want or do not want something- from birth, there always seems to be something we have to pick.

My identity is no different. The closest I’ve found to a gender identity that fully suits me is the phrase “Woman (Kind of)”. Because, though I often identify with femininity and the concept and community of womanhood, the label “woman” is just not something that sits with me. It’s something that has always been attributed to me that I went with, but never felt an earth-shattering connection to. Growing up I never voiced or complained about this. I knew about the concept of dysphoria, which the Oxford Dictionary defines as “a state of worry or general unhappiness”, but didn’t quite feel that label synced with what I felt, either. Being called “she” didn’t make me unhappy or upset, just…neutral.

I didn’t feel worthy of the space it would take to completely shift to using gender neutral pronouns without the sense of dysphoria I’d heard so many of my friends talk about. The kind that haunts them into silent shells of who they could be. The kind that has killed thousands of trans youth across the globe. I didn’t feel like the twinge of “not quite” I feel when people tell me I’m a “strong, independent woman” or a “brave woman” or even a “smart woman” was enough to push an entire narrative switch. Especially as someone who has always existed in the middle.

I am Black, but raised and trained in white spaces, so I’m the “oreo” of my family: Black and strong on the outside but white and weak on the inside because I “talk white” and “waste time” in higher education. I am Bisexual, but for the longest time I was told that my queerness was just because I hadn’t yet “found the right man”, and now that I’m in a relationship with someone who isn’t a girl I’m told it was just a “phase” until I found my place.

So of course I wouldn’t make a fuss about, once again, being in the middle. I started using both she and they pronouns towards the end of undergrad and experienced a wave of euphoria-outlined peace every time someone chose the “they” to refer to me. It was affirming. Fun. I felt seen. Whereas “she” still has the same response as someone saying what year it happens to be; it is fact, it helps me contextualize. Something I’m used to and not mad at it.

Coming into graduate school, I had the opportunity to add a preferred pronoun to all of EMU’s system. Again, I was stuck between which part of myself to use because, in the system, I was not able to put both “she” and “they” pronouns. But, ultimately, I chose to put “They” because I figured a little extra affirmation would probably help my educational journey.

And…Nothing happened. At all. My professors are usually pretty solid, but of the 6 I’ve had I can only remember 2 of them ever making a point to ask about pronouns in class and none of them have ever used the “they” pronoun for me. Ever.

I never said anything about it because I’m raised to not make a fuss about these things, “she” is something that I respond to, and I didn’t think writing my pronouns in the system would help anyway, but I can’t help but wonder- if my pronouns were never honored, were anyone’s? And what would it mean to a student who did experience dysphoria day in and out of the classroom, feeling unable to say anything beyond what they had already put into their student information?

It is not lost on me that the two professors who did make a point to discuss gender and identity had the classes I flourished in. Because it makes a very real, very noticeable difference to be seen. When people “they” me, I feel like everything’s okay. Like I don’t have to be stuck in the middle, choosing which identity to put forward to be the least inconvenient.

Concluding Comments from Amy Finkenbine, Director of EMU's LGBT Resource Center

This was a brief window into the life of just one student, Genera Fields (they/she), Graduate Assistant for the Women’s Resource Center. As the Interim Director for our affinity centers on campus, i.e. the Center of Race and Ethnicity, the LGBT Resource Center, and the Women’s Resource Center, Genera’s story is unique, but also not uncommon across our campus’ classrooms. As they shared, the importance of nurturing and recognizing a student’s affirmed identity within academic spaces can be critical to their academic success. Effective teaching and learning strategies can be pulled from many different adult learning and student development theories. From Maslow to behaviorism to Chickering, back through social or experiential, each educator can make choices grounded in theory and practice that incorporate easy wins for creating the best learning environment for their students. For this upcoming Trans Day of Visibility, I encourage faculty across disciplines to find ways to recognize, practice, and use a student’s affirmed name and pronouns within their classrooms. If you’re wondering where to start, check out our LGBT Resource Center’s upcoming collaboration with the Faculty Development Center on March 23rd, to learn more!

March 14, 2022

The Impact of Feedback on Student-Faculty Relationships by Lauren Trejo, Former EMU Communication Sciences and Disorders graduate student (Dec 2021 graduate)

The concept of feedback is engrained in students from an early age, resulting in most students being very familiar with receiving feedback by the time they pursue higher education. Feedback can impact how the students feel about a course, course content, or the course instructor. The process of feedback is straightforward on the surface: the instructor reviews a student’s work or performance and then gives information on what was done well and what could be done better. However, feedback can be complex when diving deeper into the different types of language that can be used. Directive feedback typically includes specific suggestions to the student; however, nondirective feedback in contrast aims to prompt the student to reflect deeper on their work and does not offer a specific, concrete suggestion. Critical feedback points out mistakes or errors but does not offer suggestions or instructions to resolve them, while supportive feedback aims to encourage or affirm the work of the student. In addition to considering the type of feedback given, faculty may give feedback in writing, verbally, or in a combination of the two.

In my master’s thesis research, I studied how types of feedback influenced and impacted the students and if it had any effect on their relationships with faculty both inside and outside of the classroom. We know from the literature that college students benefit from positive interactions with faculty and that graduate students in particular view their relationships with faculty as one of the key factors in how they perceive their education. I explored graduate students’ perspectives, thoughts, and attitudes on feedback experiences they recalled as being “pleasant” or “unpleasant” throughout their programs. I also asked them to react to mock written feedback. What I discovered from this study was that these students did in fact have very strong reactions to feedback types and less strong reactions to the modalities of written or verbal feedback being used. .

Students that received feedback with minimal supportive comments or nondirective comments responded with feelings of “shutting down” that led them to limit their interactions with faculty both in and outside of class. Students avoided interacting with faculty who gave them this type of feedback, preferring to rely on classmates to get assistance rather than speaking directly with the professor. In contrast, feedback that was both supportive and constructive in nature was perceived to have benefitted them the most and caused them to feel much more comfortable not only interacting with faculty in class but seeking them out outside of class as well.

Students expressed having mixed preferences regarding the mode of feedback delivery. Some students found a mixture of both verbal and written feedback to be the most beneficial as the verbal feedback was “immediate and specific” and they enjoyed being able to reference the written feedback multiple times due to it being “more concrete”. Other students expressed that verbal feedback allowed for professors to “explain things better” and allowed for further clarification in the moment. Written feedback was viewed as more ambiguous at times with it being easier to take things out of context. These findings of my research study revealed that there is in fact a connection between the types of feedback used and students’ perceived approachability of faculty following their feedback experience. To ensure best feedback practices and subsequent relationships with their students, faculty members need to examine their current feedback practices, including language and modalities used to identify any barriers they may unintentionally be creating.

To make your feedback as impactful as possible and increase the likelihood of students coming to you for support, begin by creating a space where students can be active participants in the discussion of their feedback rather than passive listeners. Disclose at the beginning of the semester your own feelings towards feedback and what its intended purpose is in your course and classroom. You can also consider incorporating a feedback preference survey to be completed by students. This would allow you to see which students prefer written, verbal, or both and would allow you to tailor your current practices in ways that will align best with their learning preferences.

Perhaps the most important piece to consider in modifying your feedback styles is to be very aware of the language that you are using. As faculty members you need to not only think of what you are saying but also how you are saying it. When giving written feedback, this may look like reading through your feedback comments a second time with the lens of a student and imagining how you would feel if you were the student receiving that comment. Are there excessive comments or critiques? If yes, consider reviewing what the student did well and add in some comments acknowledging their strengths. Punctuation matters. Almost all the students from my study reported that written feedback came across with a much more negative tone if it lacked the occasional exclamation mark. This element caused students to feel more comfortable with the faculty and increased their likelihood of engaging with them. When giving verbal feedback, be mindful of the tone of voice and body language that is being used. Are you allowing the student to share their perspective or thoughts in this process or simply reiterating what was done correctly or incorrectly? Students conveyed that verbal feedback delivered with the faculty merely listing all the mistakes and failing to ask the students their own thoughts hindered the student in feeling comfortable asking further questions, which might lead to more of an open discussion. Implementing some of these practices will likely increase your overall approachability as perceived by students and will decrease students avoiding reaching out to you for further support.

Consider that not one feedback type or modality will be effective for all your students. Creating modifications to your current feedback styles and preferences to meet the students where they are most successful will allow for greater opportunities for relationships between students and faculty to grow. We know from the literature this is extremely beneficial in students’ higher education experiences.

March 7, 2022

Jessi Kwek, Undergraduate Student

What Your Students Wish You Knew by Jessi Kwek and Hannah LaFleur, Faculty Development Center Student Workers

Generation Z knows how easy it is to forget that behind every online interaction is a whole human being – we've been dealing with the complexities of online identities since we could remember. In these last two years, Zoom and asynchronous online courses have proven this once again. This time, though, the anonymity is not taking place on social media or in a game. Instead, it’s taking place in a setting we never expected it might, one that used to be quite intimate: the classroom.

We recognize that we are not alone in our struggles – faculty have also been presented with countless challenges in the last two years – as we try to traverse this uncharted territory without adjusting our expectations for productivity or the way we measure it.

There’s been no shortage of acknowledgement about COVID-19’s impact on mental health, feelings of isolation, and disconnection from our peers and colleagues. Dr. Mays Imad, the keynote speaker for the FDC’s CONNECT Conference, has been one person leading the charge on this issue. One way that she’s been doing this is conversing with students around the country, and our conversation with Dr. Imad and six other Eastern students about our experiences over the past two years made clear that this widespread acknowledgement by teachers, administrators, and peers has in many cases not translated into tangible action to recreate those connections and curb those feelings of isolation.

In the experiences of this group of students, synchronous Zoom or in-person classes, and to a greater extent asynchronous classes, have felt like our person matters less than our EID. For many, asynchronous classes have meant we are handed a list of deadlines and left to our own devices (literally) to teach ourselves the material and stay on pace with little to no guidance from our professors. Even in the most “normal” scenario – fully in-person classes – interaction with teachers and classmates outside of direct class time is more limited and more formalized. In every one of these scenarios, there is less of an opportunity to see students as whole human beings, which is what we have been missing the most. It feels as though the student voice has been reduced to a whisper; we feel less connection to the university, our teachers, and those who could help guide us through these times.

Hannah LaFleur, Undergraduate Student

This is not to say that the burden should fall entirely upon teachers – far from it. Faculty are, in many cases, facing similar challenges with pandemic teaching as students are with pandemic learning: disconnection, distractions at home, and interactions that have lost their depth. Students understand that. The problem is that students are feeling overlooked in almost every aspect of their lives.

While mental health has become a priority in our broader community, students in this conversation reported facing CAPS waiting times of up to four to six weeks. While essential workers were hailed early in the pandemic, that sentiment has worn off, but many EMU students still have no choice but to work these low wage jobs where they cannot work from home, and they have no choice but to prioritize their employment over their safety. While the university previously implemented policies to ease the struggles of students, such as waiving online class fees and expanding pass/fail options, these have expired and we are once again subject to these less flexible conditions despite the fact that obstacles that warranted this response have not gone away. Students' options for advocating for themselves have thinned – one student in our discussion even shared an experience where she was summarily turned away by the secretary for the dean of her college when she reached out for help.

Faculty enter this conversation because they have more opportunities to see students as whole people, and to understand that the problems we are facing outside of the classroom are not separate from those we face in the classroom. Some teachers already make an effort to do this, and please trust us when we say that that effort does not go unnoticed, no matter how it presents itself. We’ve had teachers who set aside the first ten minutes of class for students to talk about current events. We’ve had teachers who know that sharing questions or comments is harder over Zoom, so they offer anonymous feedback options at the end of each class. We’ve had teachers who leave the Zoom meeting open after class ends, so students have the chance to stick around and chat after class if they’d like to. We’ve even had teachers who do something as small as asking us how we’re doing each class, and meaning it, and maybe even extending an invitation to talk if we feel the need to. Meeting students with humility and grace is powerful, and may look different for each individual.

Participants in the student session pictured with Dr. Mays Imad

We notice each one of these gestures and deeply appreciate them. These simple efforts send the message that a classroom is a safe space to acknowledge and balance issues from all parts of our lives, rather than being expected to leave whole parts of ourselves at the door to clear space for a single class. Allowing students to take up space and to bring our whole selves into the classroom has an incredible effect on our ability to learn in a more meaningful way, much as Dr. Imad suggested. Many of us are struggling to feel like a valued part of this institution, and struggling to balance the role of ‘student’ with many other roles. Each of these efforts to show students that we are seen as whole, valuable human beings on our own goes a long way. Knowing that we have a voice somewhere among the often overwhelming feelings of powerlessness makes all the difference. We want to thank the teachers who go out of their way to connect with us beyond course material, and encourage those who may not have realized how much we need this to do so, in whatever way you can. We promise you, it will be worth it.

February 21, 2022

Starfish, and You: Supporting EMU Students by Tracey Sonntag, Interim Associate Director, Holman Success Center

One thing about the Holman Success Center: we assess everything. Everything. We even assess our assessments. Of course, we can assess until we're blue in the face, but it won't matter unless we act on those assessments.

Back in 2017, EMU began implementing the early-alert tool, Starfish, in a very limited way. I've been fortunate enough to work with this tool as an instructor and Academic Success Coach for several years now, and have just recently assumed the tenant admin duties upon Raechel Epinoza's departure from the university. It has been fascinating to be involved in the back end and witness the coordination and development first-hand. Starfish is like a mythical creature with multiple arms, each reaching a hand out to every student on this campus and offering our collective engagement, support, and feedback.

Or, you know, a web-based implement providing holistic student services.

Goals and Metrics

So, you thought this post was going to be about assessment. Oh, it is. I can already share with you some of our baseline metrics.

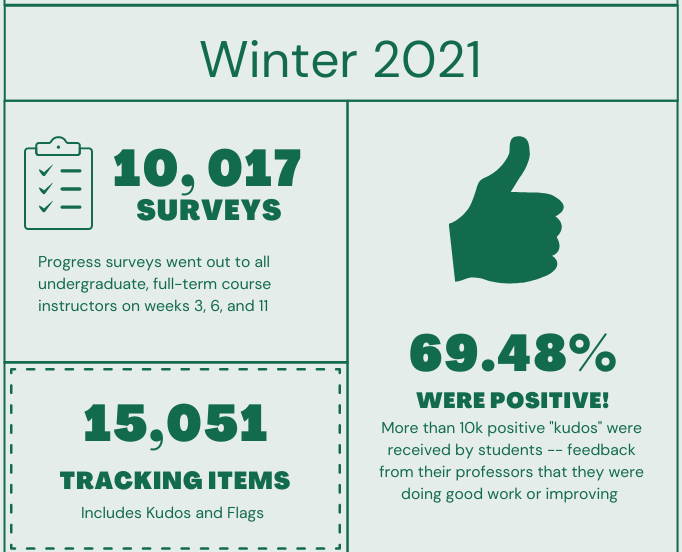

For Winter 2021, 10,017 surveys went out to instructors - one each at the 3rd, 6th, and 11th weeks, resulting in 15,051 tracking items. Even better, the items raised on these surveys were overwhelmingly positive: nearly 70% were kudos! That's more than 10,000 individual pieces of positive and motivating instructor feedback hitting our students' email inboxes.

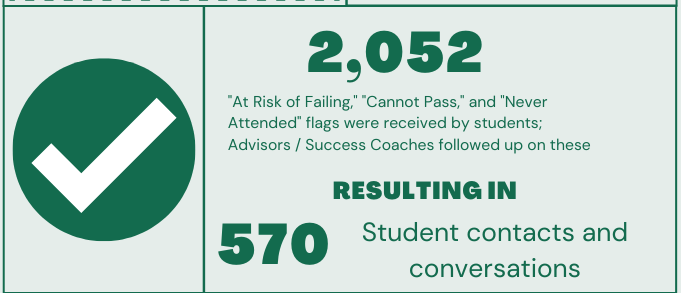

But what about the constructive feedback? The remaining 4,594 tracking items were flags of either "Attendance Concern," "At Risk of Failing," "Missing/Late Assignments," "Low or No Online Participation," "Cannot Pass," and "Never Attended." Academic Advisors and Holman Success Coaches conducted student outreach on three of these types of flags (2,052), resulting in 570 successful student contacts and conversations.

"But Tracey," you're saying, "these are just numbers. You're not assessing; you're just counting." That's fair, but our next step will be evaluating the effectiveness of instructor feedback. With all other factors being equal, what effect do kudos have on students' success in the classroom? Do students who respond to an "At Risk of Failing" flag ultimately pass the course in greater numbers than those who don't respond? We will have a lot of attributes to control for, so those data might take a while longer.

Opportunities

The ability to connect with groups of students by attribute is especially exciting to me. As an example, just moments ago, I was able to filter for all undergraduate students enrolled in a section of EXSC 201 and 202. Using this filter, I sent a brief message to all these students advertising new tutoring days and times for these courses.

Earlier today, I created a referral for one student to the Disability Resource Center, referred another student to their appropriate academic advising office, and created kudos for all of our returning EMU Edge students.

Academic advisors can pull up a list of students on their caseloads who have already withdrawn from a course in the current term, thus providing an opportunity for outreach and connection to those students who may be experiencing personal difficulties that affect their academic work.

In the Holman Success Center, we piloted the use of a personalized Success Plan for Edge students in the Fall 2021 semester. Based on student and coach feedback, we've begun creating success plans for all the students with whom we work as Success Coaches. UACDC has also been using success plans for reinstated students, providing accessible information to all support staff on individual student goals and requirements. I'm also in discussions with Sara Bamrick, Engagement and Activities Coordinator for Campus Life, on the potential use of the Success Plan tool in Starfish for a co-curricular map for students.

Future Plans

I've already had the opportunity to host training workshops for instructors and staff members on using Starfish, including best practices and the technical details of setting up appointment scheduling, viewing students by attribute, and documenting student outreach. More training sessions are being added to the calendar for early March. Our ultimate goal, on the training side of things, is to ensure that every faculty advisor and student-facing staff member is comfortable using the tool.

The Starfish Core Team is looking at more short-term goals now, such as increasing our survey completion rate up to the 40% range. For us to reach that goal, we need faculty help. It only takes a few moments to respond to each of the three Progress Surveys we send throughout the term. When you check "Low or No Online Participation" for one of your students, you are quite literally raising a flag that will catch the attention of a success coach and/or academic advisor, as well as coordinators for any programs in which the student may be participating.

While it may take a village to raise a child, we're relying on a Starfish to help us guide and support that same child to a college degree.

February 14, 2022

An Institutional Culture of Teaching and Scholarship by Erica Goff, Director of the Office of Research Development and Administration

“How do we give ourselves grace?”

She asked the question slowly, almost as if she surprised herself.

She was referring to academia, to how much of her experience, both as student and faculty, felt continually competitive; one in which enough is never enough.

She described a “culture of overwork;” a place in which “the more you can pile up … the more impressive it feels to everybody.” She described a sort of chase; for recognition, for awards, for tenure. She said she was “disappointed by the lack of acknowledgement” of her work.

She called it “unfortunate.”

She was one of a group of early career faculty who, as research participants, took time to help me understand their perspective of faculty life, particularly in relation to their institution’s culture and their own sense of success. The stories each shared with me about their experience as tenure-track faculty served as data for my own research. I identified answers to my research questions, and I learned a lot more.

For example, I learned those questions are tied directly to her experiences as an eager graduate student; as a struggling doctoral fellow at one university; a distinguished doc fellow at another; an unappreciated adjunct; and a new tenure-track faculty member. I learned that like all faculty, she was impacted by institutional culture while also participating in that culture.

In order to be accepted in their professional life, to achieve acceptance in any discipline, I learned that faculty must demonstrate a level of competence in and acceptance of the culture’s norms and values; they subsequently pass those norms and values on to their students. Students are subsequently socialized via interaction with faculty and peers, Gardner and Veliz reported, and are “integrated into the department’s activities and the culture of their disciplines.”

I also learned culture matters. While seeking answers to my research questions, I found a new question: What role do I, and my office, play within the institutional culture?

Eastern is a teaching university. EMU is also home to some very impressive research and creative scholarship. There is an acknowledgement that teaching and research/scholarship are of value, not mutually exclusive but reinforcing. That concept is fundamental to what I consider to be the responsibilities of the Office of Research Development and Administration (ORDA) in relation to institutional culture, which is much more than an office that simply moves paperwork and seems to exist simply to say “no” and obsess over rules and policies.

I envision ORDA to be a fundamental component of the culture, a resource for faculty as they seek their comfort zone in relation to balancing teaching and scholarship. The elemental role of ORDA is to help find, build and maintain that ideal intersection of (X) teaching and (Y) scholarship, a fairly individualized space in which each faculty member can feel accomplished, valued and successful, whatever that looks like for them.

So, back to the how: How do we foster a space that affords a sense of grace, of self-validation and of continued motivation?

An institutional commitment to recognition of faculty efforts across the board – across activities, across discipline, across campus– is constitutive. All recognition is meaningful, and some can be fairly simple: A mention in campus press; a university-wide announcement of an award or publication. Some must be targeted, advanced and strategic: Consistent and cohesive investment of resources from offices like ORDA and Faculty Development Center (FDC) to accurately address faculty needs as defined by faculty. It can range from procurement of specialized software to requesting appropriate lab space to advocating for procedure and policy changes. It includes advocacy for meaningful commitments to scholarship in institutional strategy. It is our job to foster, for faculty, a sense of achievement; of being valued; of professional success.

This process is collaborative and cyclical: It is one in which the establishment and clarification of expectations serves to benefit all stakeholders.

You, as faculty, are fundamental stakeholders, charged with guiding students as they stagger through the maze that is higher education. Those students, too, are critical; they are not simply numbers or dollars or opportunities for cheap labor. They are, like faculty, essential to institutional functionality and purpose. Their contributions to and participation in university life and institutional culture are significant, and they too are influenced by that culture.

Likewise, the socialization process for new faculty effectually teaches the norms, standards and values of the institution. Gardner and Veliz described a process in which new faculty “watch and learn how their more senior peers have advanced and succeeded in the unit and receive feedback on their own progress toward the goals of promotion and tenure.”

I’ll save you the boring details about framework and theory and get to the point: When aspects of the student experience, faculty experience and institutional messaging and identity are aligned, both in messaging and in action, all stakeholders benefit.

I also learned something intimately fundamental to the how and the why of academic life. It can somehow be flexible and chaotic at the same time. It is often fueled by passion, for the students and their futures; for the free exchange of ideas; for the desire to contribute to the field, the process of examining that portion of the world to which one has dedicated an entire life and career. It is a commitment to embrace a deeply specific piece of the world, to pick it up and turn it about, to examine it from every possible angle and know it better than anyone.

My own research and passion is intertwined with yours. It is to play a role in and contribute to an institutional culture that recognizes the significance of scholarship and commitment to teaching, while also recognizing and respecting efforts in service. My sense of professional success is directly correlated to my own meaningful engagement with that institutional culture.

Culture requires a team, an intertwining of many voices; individual voices that McDermott & Varenne said are “brought to life and made significant by the other….” Thank you all for allowing me to add my voice; I’m immensely excited to hear all of yours.

February 7, 2022

My Fulbright Experience in Seoul, South Korea during a Global Pandemic by Susan Badger Booth, Professor of Arts Management, School of Communication, Media, and Theatre Arts

Ambiguity, uncertainty, and doubt are all feelings I try to avoid, yet the ability to manage ambiguity is one of those talents that continues to make the list of top skills employers are looking for in new hires. Creating ambiguous and uncertain challenges for my students in my classes introduces these situations in a safe and supportive environment. The COVID19 pandemic has forced us to pivot toward a mode of managing great uncertainty in fast-changing times. As I arrived in Seoul on February 14, 2020 to begin my Fulbright semester, feelings of uncertainty and ambiguity were top of mind. Plans for my semester included both teaching (at Hongik University) and research. I would be teaching an entry level class to undergraduate students in Arts Management and a graduate level class in Cultural Planning. My graduate students and I planned to conduct focus groups in collaboration with a local cultural organization. Yet, it didn’t take long for me to realize that I would need to embrace change if my semester was going to be successful.

Fortunately, Korea was managing this public health crisis brilliantly, as they had already been tested by the earlier SARS epidemic and they have a well-developed national healthcare program in place. Soon Korean universities (including mine) would delay the semester start (originally March 1) by two weeks, and classes were moving online for at least 2 weeks before meeting face-to-face. As was happening at Eastern, we stumbled through the first few weeks, but figured out how to deliver content and share knowledge with our students from the eerily quiet classrooms we created in our kitchens and guest rooms. Two weeks online would turn to 4 weeks and eventually the whole semester would be delivered on-line.

Then on March 19 I received a message from the U.S. Department of State, Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs announcing that the U.S. Fulbright Program would be suspended worldwide, effective immediately, urging all U.S. Fulbright grantees to return home. My grant status had been moved from Fulbright Scholar to Fulbright Alumni overnight; I had until April 13 to return to the US. This was the first in a series of honest yet confusing communications from the Fulbright Office in Washington, D.C. Richly ambiguous and filled with doubt, my situation would change daily for the next week or so. It was only through the patience and fortitude of the local Korean Fulbright Office, the leadership of their board and staff, and their drive to turn outward and focus on the needs of their grantees that the program was able to allow a number of us to stay in Korea.

The EMU administration was equally supportive as I moved my Fulbright Grant to an International Visiting Professor position. Hongik University graciously accepted me in this new role with the same responsibilities. The Korean Fulbright Program showed great transparency and candor as they negotiated dozens of individual and unique situations with each grantee. They helped us with additional health insurance, return transportation, and even housing. They were exemplary at managing change and ambiguity and it is only because of their actions that I was able to continue to teach and work with my Korean colleagues.

Susan with Hongik colleague Dr. Woong Jo Chang

Unlike other parts of the world, Korea never moved into lock-down as you experienced here in the US. Instead, everyone was required to wear masks (provided by the government), and a highly developed track-and-trace system was used. Restaurants and many businesses stayed open. Unfortunately, theatres, orchestras and museums were closed for much of my semester. I was not able to conduct in-person focus groups with my graduate students, but instead enlisted my international students from my undergraduate class as our research subjects. In addition, students in the undergraduate class curated an on-line gallery show of Hongik Student Artists as their capstone project. As the Korean university is very focused on the traditional teach and test model, this applied learning style was challenging for students. I was impressed at how determined they were to create final products in both classes that were worthy of their time and effort. The fact that all of this was completed in a second language and in an online format they were not used to was additionally impressive.

This experience led me to question how I teach managing uncertainty to my students, as I often will intentionally create open ended scenarios heavy with uncertainty for my students to consider. Could sharing my own doubts, and offering them as working models for my students, be another method to help my students become more comfortable with uncertainty? Living through uncertain moments reminds us of our capacity for both resilience and empathy. Managing ambiguity may cause doubt, but with tolerance and acceptance we can cope with change and take a step toward renewal.

Although not what I had planned for a semester abroad, I created lasting friendships with my colleagues at Hongik, many of my students, and my fellow Fulbright cohort. The Korean Fulbright office continued to provide us with monthly professional development workshops – even after our status moved to “alumni”. Yes, I even met Ban Ki-moon, 8th Secretary General of the United Nations! I am already creating plans to return to Hongik and continue building on relationships kindled by my Fulbright semester.

January 31, 2022

New Opportunities in Textbook Affordability by Nick Romerhausen, Associate Professor of Communication; Director of the Introductory Course

In Fall of 2017, when I stepped into my role as the Introductory Course Director for all sections of COMM 124: Foundations of Speech Communication, I inherited an assigned textbook that was popular and from a major publisher. I had used it when I taught the course for Winter break compressed courses and it seemed like all the other textbooks I had taught from during my years as a graduate student—in a good way.

The countless introductory textbooks on the market all should seem like one another. Sure, some have brighter photos and some have more student-centric covers, but they all are going to have the same material for any introductory public speaking course. Chapters on speech apprehension, informative speaking, persuasive speaking, delivery techniques, outlining, and researching should be included in any text. So, the book we had worked just fine.

Over the next two years, I learned a lot from my graduate teaching assistants, especially when we were involuntarily moved to a “new” and more expensive edition by our publisher. Although we used the textbook for content and also directly connected it to writing and speaking assignments, the graduate student instructors were dismayed by the number of students who didn’t purchase the book. Many hoped that a friend would share or that they could get by without it. At this moment, I didn’t realize that in recent years something had changed in the way instructors at universities around the country were becoming part of a new movement in textbook affordability.

In the Fall of 2019, when I was struggling with how to get more students to access the text, I received a serendipitous email from University Librarian Kate Pittsley-Sousa, who heads up EMU’s Textbook Affordability Initiative. After a phone call and a meeting with Kate, I was intrigued when I learned that there might be an opportunity to find a zero-cost open educational resource textbook.

With textbooks classified as OERs, the authors hold copyrights but make their works available to be distributed to the open market at no cost to the consumer. Additionally, many of these books carry a license that allows users to add, edit, or delete content. They are inspired by the open source movement in software. Authors do not intend to make money; some don’t even have the intention of being credited for their work. In the case of many authors, the interest has been in making information available to students.

I had to see if this was possible for us. I immediately had my graduate teaching assistants work on a textbook search with me to find potential texts by Googling terms such as communication, public speaking, open source, and open license. We found a very well-written book that was created in 2014 but had not been updated and looked like it was not going to be. There was a promising book from a community college that was written specifically for students at that school. We would be free to rewrite and change content as needed because of the open source license, but the laborious task of finding all the references to that specific college, rewriting the chapter on navigating their university’s library system, and deleting or rewriting other nuanced references seemed to be too much. However, we found some good candidates and finally in early 2020 landed on one from Dalton State University in Georgia entitled Exploring Public Speaking.

The authors have an open license and tell users directly on their website, “you can edit and add/subtract as you like, as long as we get the original credit and nothing is sold.” The homepage has accessible PDF versions, rewritable Word versions, a Kindle version, worksheet templates for students, and rewritable PowerPoint slides for instructors. I emailed the lead author of the project and she told me that she would add any instructors who emailed her to a test bank supplement. I was sold. And I needed to be. I just finished consulting with a graduate assistant who wanted to know how to help a student in the Winter 2020 semester who did not bring their book home with them when they had to abruptly leave campus.

We piloted the text in Summer sections in 2020 and have used this text since then. Here are some of our highlights:

- Instructors can attach the text as a PDF file and attach this as a file in an email to students, on Canvas pages, and/or offer the link for other readable versions of the text if those are available.

- Our text is organized “like all the others,” and of course, this is exactly what we want. The content is accurate, continually updated, and directly matches our Student Learning Outcomes.

- Because we found a particular book with active authors, we are now part of a community. The authoring faculty at Dalton State indicated that they had received a grant to support this process in making textbooks affordable, and therefore, they have an incentive to make a significant impact. I am on an email list with faculty from who use the text at other universities. A few weeks ago we all received updated and rewritable Powerpoint slides in a cool design that were specifically made to better match ADA standards.

- I haven’t had to consult with any instructor about a student who can’t access the textbook.

Of course, there are some drawbacks:

- Many books might have been written at one time or for students at a specific institution and may not have active authors who are involved in the continual management of the text. There might be texts that are incomplete, written poorly, incomplete or simply do not meet your course.

- Flashy pictures are replaced with stock images and some versions might not have much visual content since flashy images cost money.

- All books are Ebooks that are downloadable (usually as PDFs) so the nostalgic feeling of thumbing through a new college textbook, or even the smell of it, is gone.

- While I had success in finding this book for our introductory course, I have not fared as well in finding OER books for upper division courses. In our discipline, the books for foundational classes have open access versions as that seems to be where the most impact can be made on students.

Nonetheless, in my current experience, the “no cost” benefits significantly outweigh the costs. The movement of OER textbooks is clearly growing. More and more faculty are adopting the book I am currently using each and every year. Organizations such as The William and Flora Hewlett Foundation are funding more grants each year for this specific endeavor. Panels at conferences in our discipline (and I am sure in many of your disciplines too) are addressing the topic. I encourage any instructor who is concerned about cost as a barrier to access to contact Kate Pittsley-Sousa and start Googling to see if there is something out there to match a course that you teach in your discipline.

January 24, 2022

Social Presence and Teacher Transparency in the (Pandemic) Classroom by Sarah M. Ginsberg, Professor, Special Education and Communication Sciences and Disorders

At the heart of any good classroom dynamic, whether in person or online, during a pandemic or so-called normal circumstances, lies a willingness for students to talk, ask questions, and share their perspective. As an instructor, these interactions contribute to my sense of the students’ engagement with the material. Social presence, which became popular in the mid-1990’s, was described as the sense of personal connection students have with other learners, or a feeling of community, in an online learning environment. Research about social presence demonstrated that learners need to have a sense of who they are learning with (peers) and who they are learning from (instructor) in order to experience satisfaction with learning in an online course. I suspect that students who have a clear sense of who they are learning with and from in face-to-face learning contexts experience similar satisfaction and increased comfort in being willing to actively engage in the classroom through asking questions and sharing their thoughts.

I first came across this literature in the early 2000’s as I was conducting research about the influence of faculty classroom communication on students’ perspectives about the instructor. In my grounded theory research, I developed the idea of teacher transparency. Transparent teachers communicate to their students who they are as people as well as their views of teaching and learning. In this study students were able to articulate insights into the transparent teachers’ caring and reflective nature and accurately describe their instructors’ perspectives on teaching and learning. The students of transparent teachers also reported being motivated to work hard in their courses. Related to social presence, teacher transparency resulted in increased student engagement by giving students a sense of who they are learning from.

So how do we give the students the information that they need to feel safe and willing to engage in learning during online or in person classes? There are any number of approaches that you might use to increase both social presence and teacher transparency. I will share three steps that I implement, many from the beginning of the semester. On the first day of class (in person or online) I have the students get into small groups to meet each other and exchange contact information for the purpose of supporting each other throughout the semester. Then I give the group the task of creating a list of questions for me as the instructor. My directions are “you can ask me anything that you think would make you more comfortable learning in this class.” Creating the list of questions is often their first interaction and allows them to begin working together. It also gives them a chance to ask a question as a group so that asking the question doesn’t make them feel vulnerable. I have never had to decline to answer a question because it was inappropriate or too personal, but I will say that many of their questions are thought provoking and create opportunities for me to share small innocuous details about myself that allow them to develop a sense of who I am (such as my area of research or that chocolate is the way to my heart). Anecdotally, this exercise often gives me a strong sense of how lively the class discussions will be over the coming semester, and how hard I will have to work at drawing them into discussions.

The second step I take is sharing a statement of my teaching philosophy in my syllabus. I share several points, including “anxiety is the antithesis of learning.” I explain each briefly in the syllabus, and I spend time talking about their implications for our learning space. I reinforce my philosophy throughout the semester by referring back to what I have written and shared. I will say to them, “Are you feeling anxious about this project? If you are, let’s talk about it so that you can focus on learning.” Over the course of the semester I will show “how do you feel today?” memes at the beginning of class and check in with them about how they are doing. This gives them a moment to share with me and with each other thoughts they might be having, or stress they are sharing. It creates the space for them to connect and tells them that I care about how they are doing.

The third item takes some time from teaching, but I find that it is worth every minute. At the beginning of the term, particularly when I have a new cohort of students, I ask them to introduce themselves by sharing something about themselves. My favorite ice-breaker questions are “something people are surprised to learn about me is…” or “something that I am really proud of …” Their responses give all of us a sense of who is in the class and how they see themselves. It is often impressive how many students have shared interests. The realization that they have common interests helps them become comfortable with each other as learners. Throughout the semester, particularly when we have been fully online, and the students don’t have the opportunity to interact informally, I create small group activities during class through breakout rooms. For each application-based activity I specify for them the goal of the task, the steps they will need to take to complete the task, and the time frame to complete it. As I pop in and out of breakout rooms checking on their progress, I give them just an extra minute or two beyond what the task actually requires so that they can interact informally. These extra few minutes allow them to forge connections with each other and furthers their sense of who they are learning alongside.

One of the takeaway lessons from both the concepts of teacher transparency and social presence is that students will be more engaged in classroom learning when they have a sense of who is in the learning community with them. There are a wide variety of methods that you might use; you may be doing some of them already. The tips shared here are ones that I have learned along the way, mostly from outstanding teaching colleagues. I can’t take credit for inventing them, just for adapting them to make them my own. I would encourage you to consider what you would want to know about people in a learning community in order to feel comfortable actively engaging in discussions. Find ways to improve the sense of connection that everyone feels with each other that are consistent with who you are as an instructor. Communication approaches consistent with your most authentic self as an instructor will be most successful and will hopefully yield a more engaged group of students in your courses.

January 17, 2022

What’s the Story? by Edward Sidlow, Professor, Political Science

I walked into the room where our department faculty meetings were held. Several faculty members were there and the meeting was to start in a few minutes. The department head had not yet arrived. One faculty member engaged in a diatribe about how miserable our students are. “They don’t do the reading. They don’t know what’s going on in the world. They don’t engage in discussion; getting them to talk is like pulling teeth. Their writing is awful, and they are not intellectually curious.” When she took a pause, I filled the void with a simple statement. “You should hear what your students say about you.” The room went silent, but at least the tirade ended.

Indeed, our students do talk about us. They claim some of us are arrogant and full of ourselves. Others are disorganized and much too slow to return written work. Still others are pushing a point of view and intolerant of students who disagree with them. Some appear not to care and are so self-absorbed and egotistical that by mid-term, students find it hard to go to class. And, the students say, more than a few professors don’t know how to dress.

But all is not lost. Some of us seem decent and caring, even compassionate. Some of us are quite organized in the presentation of our material and appear thoughtful, open to questions, handling disagreements gracefully. Some of us make class discussion fun at best and, at minimum, interesting. These professors are the ones who have full classes and waiting lists. They are also the faculty who are recommended by students to their friends. Some of us even know how to dress. There is an active and dynamic student grapevine, and yes, our students talk about us.

I served as a faculty member at three universities over the past 40+ years. The demographics differed a bit with each, but the presence and character of the student grapevine was the same across all three. I had the good fortune of being sought out by students, and while I fear appearing immodest, the grapevine spoke well of me and I won teaching awards everywhere I taught. Early on, I accepted my success grudgingly, but over time, I embraced it.

My teaching covered American politics and government and I was determined to never have my classes thought of as boring. To that end, I immersed myself in biographies of American political figures. I also did research that had me in state legislatures and Congress, and always managed better access to the players than I deserved. My projects involved interviewing legislators and/or their support staff. And every interview protocol had a question or two for the classroom. Typically, I asked what was the strangest (funniest, saddest, most gratifying) thing you’ve seen or experienced in your time here in Congress (statehouse)? The biographies and the research provided a deep well of interesting stories, and the stories were what kept students coming back. No matter how strange the story, it had to illustrate an important point in the day’s lecture or discussion. I know now that it was never me, or the academic material, that the students came to class for. It was the stories.

When I was a young faculty member in my 20s and 30s, I bristled at the comments from students to each other or on class evaluations that said, “he tells such wonderful stories.” I wanted to be a serious academic and I taught at prestigious places. I wrote articles for journals, and books. I wasn’t a damn storyteller. To get under my skin, my graduate assistant one year, who would stop at my office to pick me up for the walk to class, would say as we approached the classroom, “Let’s go tell a few good stories.”

I started teaching decades before email and the Internet. It took these technological innovations for me to recognize fully that my use of stories had real meaning in the classroom. Students from schools where I taught before I came to EMU find me on the university website, and connect with an email. Often the message will be, “I was watching the news and saw something that reminded me of a story about… that you told us in class 30 years ago.” It’s nice to be remembered.

My students have taught me that telling relevant stories can be a successful teaching strategy. I have recently retired, and have made my peace with being a storyteller. But there is another, equally important story here, and that’s the story that our students tell about us. And that story is a large part of our legacy. Our teaching, writing and academic service are the hallmarks of our professional careers. Teaching has the greatest impact on our students, and they talk about us. They go home for holidays and tell stories about their professors and their classes. I think it would serve us all well to remember that the stories that we tell in class are only part of the story, and they are certainly important. It is also wise to remember that the stories that our students tell are important as well. It is our good fortune if the stories we tell in class allow our students to tell stories about us that we can be proud of.

January 10, 2022

Checking In by Perry C Francis, Professor, Leadership and Counseling

Have you ever walked into your classroom and felt as if the students were on edge? I’m not talking about the free-floating anxiety that appears just before an exam. I’m referring to that feeling you get when the tone of the room just doesn’t feel right. Maybe they’re talking a bit too much, or there’s that eerie silence like you just walked into a mausoleum. I recall just such an occasion during the time when EMU was struggling to respond to the racist graffiti that appeared on some buildings around campus. That incident lit the flames of unrest and unease among many of our students. It was a feeling that permeated many of our classrooms; whether the subject was chemistry or cartography, photography or physics, our students were ill at ease.

It was at that moment I began to institute a check-in time with my classes. I would take the first five to ten minutes of the beginning of class and process the day’s events with my students. During the aforementioned time at EMU, it led to a rich, albeit brief, discussion about race relations on campus and how we as a community might react to it. Some student shared resources, others expressed their dismay at what was occurring on campus, and still others offered words of empathy to their fellow classmates. I listened patiently and offered whatever guidance I could and tried to guide the discussion so that all felt safe in expressing their opinions or comments.

I teach in the professional counseling graduate program and am a practicing psychotherapist, so listening and responding empathically comes naturally to me. You might even note that beginning this practice would seem to fit in a class about counseling skills, but not so much in biology or art appreciation. Besides, you might point out, there is only so much time you can spare in any given class period. But I would suggest that the simple act of checking in with your students on occasion and listening to their concerns can enhance the learning environment and help your students focus.

Often times, the simple act of talking about what concerns us or sharing those negative emotions with someone, like a trusted teacher or fellow student, can have a positive impact on our immune system, reducing distress and helping with concentration and learning. It also offers us the opportunity to learn about our students and what concerns them.

Now this might work well in a small class of 15 to 25 students, but what about those large lecture sections of general education classes held in auditoriums that require binoculars to see the back of the room? Perhaps a simple acknowledgement that you are aware of the tension on campus and an offer of information where students can go for help in processing their thoughts and emotions. A word of understanding and empathy can also be offered to demonstrate your own humanity in the midst of the turmoil.

During this time of a pandemic that seems to insist on continuing despite our best efforts, a wise colleague of mine has created an addendum to her syllabi that acknowledges the struggles of learning on-line, especially for those students who are not internet natives or struggle with technology issues due to various constraints. In it, she acknowledges the stresses and strains our current situation has on our environment. Some of our students are parents, others have medical issues that raise the stakes of getting infected, and still others just do not like Zoom learning. During the first class, she checks in with the students and shares her commitment to be flexible in this time of COVID chaos and to help each individual learn. It promotes wellness and helps learning.

What might this look like in your classroom? Cathleen Beachboard, an instructional coach and teacher, makes the simple suggestion of starting the class with a poll. This can be easily accomplished using the Zoom polling feature. The poll question can be a simple one, for example, How am I doing today? The choices can be I’m Great!, I’m OK, I’m struggling, or I am having a hard time and need some help. This will allow the students to give you anonymous information about the class, their mental state, or just how the day is going. Having a resource sheet available with different options is a way to promote student wellness, enhance learning, and sharing your humanity.

Checking in is a simple act, one that promotes wellness, and one that you can institute fairly easily. But most of all, it promotes connection between you and your students on a person-to-person level. And isn’t that what teaching is all about…making a meaningful connection with others as you share with them knowledge that will not only benefit the students, but all who come into contact with those students?

All my best to you in your teaching.